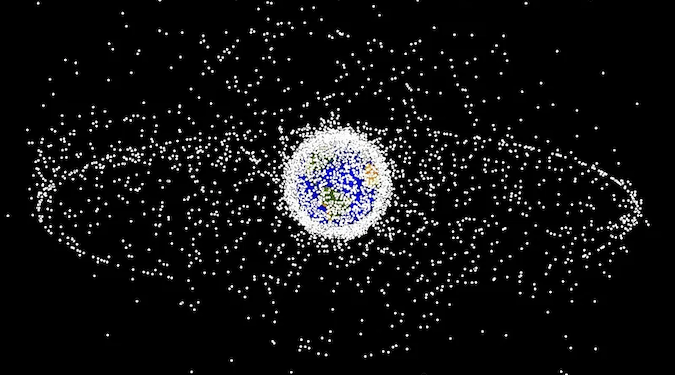

Matin Pedram and Eugenia Georgiades compare existing regulatory frameworks for Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites and argue none are robust, transparent, or efficient enough yet to curb monopolistic or rent-seeking behaviors. Likewise, Pedram and Georgiades reveal how national security concerns can be overextended to instead protect domestic space activities. Pedram and Georgiades analyze licensing requirements,… Continue reading The Role of Regulatory Frameworks in Balancing Between National Security and Competition in LEO Satellite Market

Category: International Security

Will Soper Responds to Tyler Smotherman’s Review of “Greytown Is No More!”

I have read Tyler Smotherman’s review of my book, Greytown Is No More! I am much buoyed by the many positive passages to be found throughout its 17 pages. I wish to thank the reviewer, Tyler Smotherman, JNSLP Managing Editor Todd Huntley, and Editor-in-Chief William C. Banks for their efforts. I would like to take… Continue reading Will Soper Responds to Tyler Smotherman’s Review of “Greytown Is No More!”

Commissions Impossible: How Can Future Military Commissions Avoid the Failures of Guantanamo?

Aaron Shepard endeavors to examine the roots of the failures of the Guantanamo military commissions and suggest potential solutions to remedy them. His paper begins with an introduction to the concept of military commissions, including a brief overview of their historic utilization and import. It then provides a detailed background on Guantanamo Bay, covers the… Continue reading Commissions Impossible: How Can Future Military Commissions Avoid the Failures of Guantanamo?