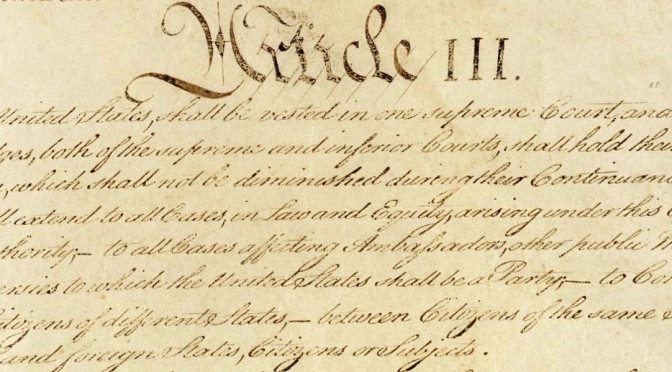

The Honorable Lewis A. Kaplan draws on his voluminous experience on the federal bench to illuminate some of the special concerns that attend terrorism and national security cases. Kaplan reviews several judicial challenges unique to terrorism cases, including classified information issues and the use of defendants’ statements in the course of prosecution. He concludes that… Continue reading The Implications of Trying National Security Cases in Article III Courts

Tag: Military Commissions

The Next Judge

The filling of a judicial vacancy provides a unique opportunity to examine not only the appointment or election process, but also the court itself and its work. For obvious reasons, this has been recognized in connection with the Supreme Court of the United States,1 where vacancies are often the subject of much conjecture but, because of life tenure, remain essentially unpredictable. On a less lofty plane, the opportunity to take stock also occurs in other courts, and the timing, at least, is less a matter of speculation in non-Article III courts, where judges serve for fixed terms.

The Laws of War as a Constitutional Limit on Military Jurisdiction

It is impossible to have a meaningful debate over whether a civilian court or a military commission is a more appropriate forum for trying terrorism suspects so long as serious questions remain over whether the commissions may constitutionally exercise jurisdiction over particular offenses and/or offenders.