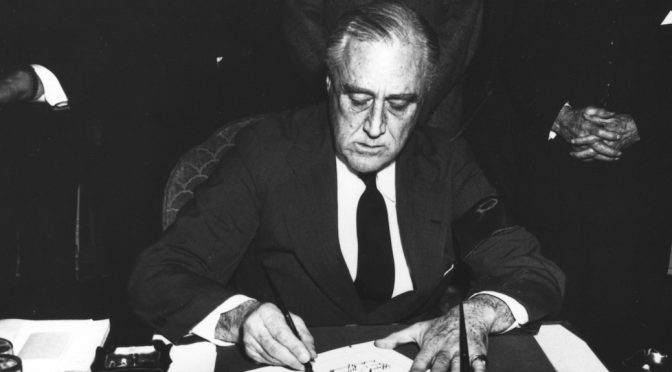

Shortly after Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued a proclamation of a “limited” national emergency. This proclamation cited no statutory or inherent authority. Alden Fletcher looks to the historical record to suggest Roosevelt’s proclamation was relying on ambiguous statutes that provided for executive power to declare emergencies or take emergency… Continue reading Roosevelt’s “Limited” National Emergency: Crisis Powers in the Emergency Proclamation and Economic Studies of 1939

Category: Vol. 12 No. 2

Reviving Liberal Constitutionalism With Originalism in Emergency Powers Doctrine

Legal scholars have theorized three models of Article II’s Executive Power clause, otherwise known as the Executive Vesting clause: first the cross-reference theory, which points to specific powers under Article II, such as the appointment power; second, the Royal Residuum theory, which interprets Article II as granting wide-ranging powers possessed by the eighteenth-century British Crown;… Continue reading Reviving Liberal Constitutionalism With Originalism in Emergency Powers Doctrine

Comparing the Strength of SEP Patent Portfolios: Leadership Intelligence for the Intelligence Community

The next generation of mobile broadband, 5G, is emerging as a major area of competition between the United States and China. 5G technology promises vast improvements not only to the speed of commercial cellular connections, but also to governments’ intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities. Leadership in the development of 5G technology has thus been deemed… Continue reading Comparing the Strength of SEP Patent Portfolios: Leadership Intelligence for the Intelligence Community